Cover Story: Addressing 2020’s Other Disaster — Accelerating Climate Change

There’s no doubt that 2020 will have a special place in history, and not just for the Covid-19 pandemic that so far has killed more than 1.8 million people. It was also a year of extreme weather disasters that showed how climate change can be fatal for humanity.

Natural calamities hit many parts of the world, from deadly wildfires engulfing California, Australia and Russia’s Siberian hinterland, to devastating summer floods in China and other Asian countries, to massive tropical storms sweeping Central America.

The frequent weather catastrophes reflected rising temperatures. Meteorologists around the world recorded 2020 as one of the hottest in history, underscoring the urgency of more aggressive global efforts to contain warming of the planet.

The global mean temperature between January and October last year was around 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than the pre-industrial 1850-1900 baseline, according to the World Meteorological Organization, an agency of the United Nations. That made 2020 one of the three warmest years on record, and it made the decade the hottest.

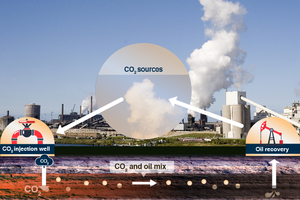

Accelerating climate change is driven by human-induced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2). Although global emissions fell by 7% in 2020 as the pandemic interrupted travel and industrial production, carbon concentrations in the atmosphere continue to rise.

According to the annual Emissions Gap Report issued in December by the United Nations Environment Program, global GHG emissions continued to grow for the third consecutive year in 2019, reaching a record high of 52.4 gigatons of carbon equivalent. CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and carbonates dominate total GHG emissions and reached a record 38 gigatons of carbon equivalent, according to the report, which analyzes the commitments that countries have made to reduce emissions and the gap with goals set in the Paris Climate Change Agreement five years ago.

Under the Paris accord of 2015, 196 countries agreed to take steps to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C compared with the pre-industrial baseline, well below 2 degrees C — the point at which scientists calculate global warming would unleash catastrophic consequences.

“We are currently not on track” to meet climate change targets, “and more efforts are needed," Petteri Taalas, secretary-general of the World Meteorological Organization, said last month.

All eyes are now on the U.N. Climate Conference of the Parties (COP26) in November in Glasgow. The meeting was postponed from 2020 because of the pandemic. Countries are expected to work out solutions for some of the unresolved issues left by the 2019 gathering, such as details on global carbon trade and capital commitments to support emission cuts.

The Glasgow conference will also be the first iteration of the ratchet mechanism set by the Paris Agreement. Under the accord, countries submitted intended nationally determined contributions to reduce GHG emissions. The targets are to be updated with enhanced goals every five years to ratchet up ambitions to mitigate climate change. However, the nonbinding arrangement has been widely criticized for lacking teeth.

Five years after the signing of Paris Agreement, the global coalition to contain climate change faces more complicated challenges from environmental, political and economic fronts. One of the major setbacks was outgoing U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the agreement. Although President-elect Joe Biden has pledged a return, experts said the world’s largest economy won’t be able to immediately overturn Trump-era climate policies.

Other major economies including China and the European Union have made commitments to further control emissions. But as countries struggle to contain and rebound from the pandemic, the massive rollout of investment-driven stimulus policies may make cutting emissions harder to accomplish.

According to a recent study by Tsinghua University in Beijing, the world needs to achieve net zero carbon emission by 2050 to reach the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C. This will require a significant revamp of the world’s industrial and energy structures.

“Five years after Paris, we are still not going in the right direction,” said U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres at the Climate Ambition Summit in December. “If we don’t change course, we may be headed for a catastrophic temperature rise of more than 3 degrees this century.”

China’s commitments

Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged that China will reach peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060. At the December Climate Ambition Summit, Xi made further commitments that the country will lower its CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by 65% from the 2005 level in 2030, increase the share of nonfossil fuels in primary energy consumption to 25%, and bring its total installed capacity of wind and solar power to more than 1.2 billion kilowatts.

China’s ambition to reduce emissions reflects the country’s own struggles with air pollution and extreme weather events like this summer’s disastrous flooding in the Yangtze River basin. China has been battling air pollution caused by excessive emissions. In 2013 as the country started to monitor air pollution caused by fine particles, 71 out of the 74 cities monitored reported high levels of pollution.

China has aggressively promoted heavy investment in renewable energy. The country has been the world top’s investor in renewable energy over the past seven years and accounts for 32% of newly installed global capacity of clean energy, according to Li Ting, representative of the Beijing office of the Rocky Mountain Institute, a think tank.

However, China remains a major user of coal, which accounted for 59% of the country’s overall energy consumption as of 2018, driven by massive demand from heavy industries and transportation. In 2017, China overtook the U.S. to become the world’s top carbon emitter.

According to He Jiankun, an environment studies professor at Tsinghua University, China’s carbon emissions will peak in 2030 if the country can cut CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by 68% from the 2005 level. After that the country’s carbon emissions will start to drop dramatically, He said.

But Li Shuo, a senior policy analyst at Green Peace, said sharp emission drops after 2030 are unlikely unless there are major technology breakthroughs.

|

Global GHG emissions continued to grow for the third consecutive year in 2019, reaching a record high of 52.4 gigatons of carbon equivalent. |

Nevertheless, experts agree that reduced reliance on coal is crucial for China to meet its emission goals. The country is expected to cut coal’s share of energy consumption below 50% during the 2021–25 period, according to Wang Weida, an energy expert at the Beijing office of the World Wide Fund for Nature.

But the pandemic may bring some uncertainties to China’s emissions control efforts as stimulus policies to boost economic recovery are likely to benefit some high-emission industries. In 2020, China’s steel and cement industry grew faster than the previous year, reflecting an investment surge to bolster the economy, according to Li Shuo. Analysts warned that policymakers should carefully design pro-growth policies after the pandemic to direct more support to clean energy, electric vehicles and other environmentally friendly industries.

Global coalition under test

China, the U.S. and the EU account for a combined 45% of global emissions and led the global talks that led to the 2015 Paris Agreement. In 2014, China and the U.S. made joint commitments on emission controls under which China promised a peak of carbon emission by 2030 while the U.S. pledging to cut its 2025 emissions by as much as 28% from the 2005 level. The EU that year also set a goal of reducing GHG emission by 40% in 2030 compared with 1990.

But the joint efforts quickly crumbled as the Trump administration withdrew the U.S. from the agreement. Trump argued that emissions control measures under the Paris Agreement would cost millions of American jobs.

As the federal government pulled back from emissions control commitments, authorities at state and city levels as well as private sector players became the main U.S. forces fighting climate change during the Trump presidency.

According to Leon Clarke at the University of Maryland, American states, cities and companies that committed to follow the Paris Agreement account for two-thirds of the country’s population and nearly half of national emissions.

In the U.S., the costs of renewable energy have fallen below those of fossil fuels, benefiting the country’s energy shift and reducing emissions, said Li Ting at the Rocky Mountain Institute.

If the momentum continues at lower levels, the U.S. will be able to fulfill its emissions reduction goal by 2030, Clarke said. But to further reduce emissions and reach a net zero goal by 2050 will require more aggressive measures led by the federal government, he said.

The Biden administration may bring about changes as the president-elect has pledged to rejoin the Paris accord after he takes office Jan. 20. But it will take time for the new administration to restore America’s climate agenda, said Li Shuo at Green Peace. The Biden administration will face budget limits and other constraints left by the Trump administration, Li said.

The ripples created by the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris accord also raised a key question for the global community: How the coalition fighting climate change can survive a major players’ policy change, Li said.

|

One of the major setbacks was outgoing U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the agreement. |

Compared with the U.S., a stronger EU public consensus on climate issues has formed, according to Clarke. The 27-country bloc relies much less on fossil fuel than China, making it easier to adopt emissions control measures. In December, the EU updated its emissions targets to a 55% reduction from the 1990 level by 2030, compared with the 40% goal set in 2014.

The EU presents a good example of how economic growth can be maintained without higher emissions, a key concern of many governments. Between 1990 and 2018, the bloc’s economy expanded 61% while its GHG emissions dropped 23%.

The EU has shifted a large portion of power generation from coal to clean energy such as wind and nuclear power. Moving forward, the EU will need to crack the next challenge of reducing emissions from the transportation sector by implementing stricter auto exhaust standards, analysts said.

But there are still gaps among EU member countries in fulfilling emissions control goals as countries like Poland and Germany have moved more slowly to reduce the use of coal.

Experts said the global coalition for emissions control is weaker than five years ago as countries like India, Japan, Brazil and Australia have been lukewarm to stepping up emission reductions, citing economic concerns.

Looking ahead to Glasgow

In December, 45 of the more than 70 countries participating in the U.N. Climate Ambition Summit presented strengthened 2030 climate plans in accordance with the Paris Agreement. According to Guterres, countries contributing two-thirds of global CO2 emissions have promised to achieve carbon neutrality, meaning net zero CO2 emissions, by balancing emissions with carbon removal.

While progress was made, experts said the plans set by individual countries are not enough for them to reach the limit of 1.5 degrees C of temperature increase under the Paris accord, not to mention uncertainties in their implementation.

Many countries face challenges to reduce carbon emissions in heavy industries and auto manufacturing as well as introducing more environmentally friendly solutions for other industries, analysts said. In addition, governments are also under pressure to balance emissions control with economic recovery in the post-pandemic era, they said.

Global leaders at the Glasgow conference need to address several key issues to further strengthen the Paris accord, Yamide Dagnet, director of climate negotiations at the World Resources Institute, wrote in a report. That includes a clear timetable for countries’ climate commitments, technology details for the global carbon trading mechanism and climate investment commitments.

Working out a carbon pricing system that can be accepted by all countries will be the most challenging issue in the design of the carbon trading mechanism, experts said. The Glasgow meeting will also evaluate the commitment made by developed countries in 2009 to provide $100 billion annually to support the fight against climate change and set up new targets for climate investment, Li Shuo said.

Whether and how the U.S. will rejoin the Paris accord will be another closely watched development this year, Li Shuo said. It is likely the U.S. will re-launch negotiations to join the agreement and push others to further strengthen their climate plans, Li Shuo said.

Contact reporter Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com).

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR