Cover Story: The Green Finance Challenge Facing China’s Banks

China’s plan to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the next four decades will put increasing pressure on a financial system that isn’t ready, according to top industry regulators and banking experts.

On the one hand, banks and other financial institutions could benefit from rising demand for tens of trillions of yuan of green financing to pay for sweeping changes throughout the economy, according to Ma Jun, a member of the monetary policy committee of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and director of the Green Finance Committee of the China Society of Finance and Banking.

On the other hand, the industry must learn to account for rising climate-change risks as they go about their business of underwriting credit, said Ye Yanfei, director general of the policy research bureau at the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC). Assets invested in companies or projects that rely on traditional and dated technologies may risk becoming stranded or losing their value, Ye said.

“Chinese banks and insurers shouldn’t only look at the interest they receive for now, but be aware that with technology and policy changes, they may be able to receive interest only for the first five years but lose their principal in the next 15 to 20 years,” Ye said.

The vast majority of Chinese financial institutions lack knowledge of climate risks and the opportunities of carbon finance, requiring deeper internal talent pools and greater capacity for acquiring external data, industry experts said. In the past, China relied more on administrative measures to prevent and control pollution. Now China needs to rely more on market and financial mechanisms, posing a significant challenge to policymakers, financial and market regulators and market participants, according to industry experts.

A key strategy for reducing emissions of carbon dioxide — the greenhouse gas that plays the biggest role in global warming — is to cap carbon emissions with regulations and allow businesses and institutions with unused carbon quotas to sell them. This puts a price on emissions and creates power financial incentives for reducing them. China needs active participation by financial institutions in carbon markets as in the European Union, a person from a financial institution told Caixin.

The main obstacles include a lack of market liquidity, lack of transparency of information, and unstable carbon quotas and policies, this person said.

“We need some speculative investors in the carbon market, whose maturity preference is different from that of enterprises,” said a senior financial researcher. “This would create different prices so as to promote market liquidity.”

The pressure to address climate change in China comes from the top. President Xi Jinping pledged in September that the world’s biggest producer of carbon dioxide aims to top out such emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. The ambitious target will require the transformation of the world’s second-largest economy to a low carbon growth pattern.

|

The transition to a zero-carbon economy is seen as a new round of the green industrial revolution. Carbon finance promises not only to create a new branch of climate finance or green finance but also to reshape the entire financial system’s assets and investment and financing activities with a low-carbon approach.

Achieving carbon neutrality will require tens of billions of yuan of green investment, most of which will require mobilizing social capital through the financial system, bringing huge opportunities for green financing, the PBOC’s Ma said.

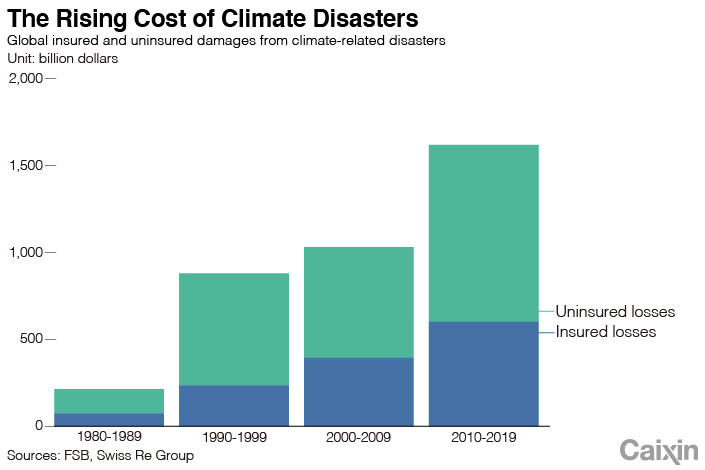

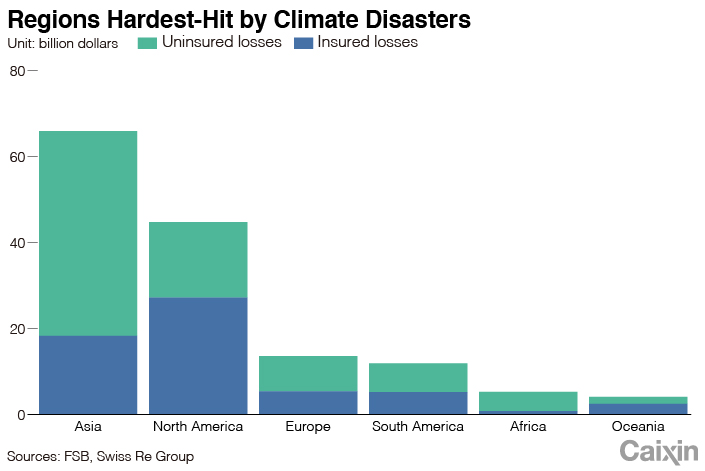

In a 2020 book the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) laid out the risks to the global financial system posed by climate change and the limitations of current models in quantifying potential impacts. The BIS called the risks a “green swan” — a play on the term “black swan,” referring to rare events that have the potential to cause extreme financial disruption. A green swan event could lead to the next systemic financial crisis, the BIS argues.

Central banks alone cannot mitigate climate change, and addressing the complex problem of collective action will require coordination among many players including governments, the private sector, civil society and the international community, the book says.

Assessing the ‘green swan’

The first task is to measure how big the green swan risks are. The main approach is to conduct climate-risk stress tests.

The importance of conducting this kind of analysis has been a focus of central banks including the Bank of England and the European Central bank as well as the Network for Greening the Financial System, a network of 83 central banks and financial supervisors. Some major financial institutions are beginning to take up the challenge. The Bank of England estimated that extreme climate change could cause $43 trillion in losses to financial assets, while the Netherlands Bank said 11% of the country’s banking assets face significant climate risks.

Most financial institutions in China have not yet fully grasped the risks associated with climate change and generally lack forward-looking risk prevention mechanisms for climate risks, the PBOC’s Ma said.

The challenges of conducting climate-risk stress tests include technical difficulty and the lack of unified methods and standards, said a person close to the PBOC. Different parameters can result in results that vary wildly, according to an Industrial Bank research team led by Chief Economist Lu Zhengwei.

In 2015, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (601398.SH) became the first Chinese bank to conduct climate-risk stress tests. The results were released during the G20’s Green Finance Summit in March 2016. ICBC used scenario analysis to assess how changing policies on thermal power, cement, electrolytic aluminum and steel industries and extreme weather conditions such as drought could affect the bank.

Compared with asset management companies, banks and insurers react more slowly to climate-change risks, said the CBIRC’s Ye. Reasons are that they do not directly face market-oriented investors, and they may focus too much on the immediate benefits of proposed projects, he said. China’s commercial banks and policy banks have assets with longer durations than their global peers, increasing potential climate-change risks he said.

|

Lack of climate information disclosure

An important foundation for climate stress tests is the disclosure of consistent, high-quality climate information. The PBOC recently started an environmental information disclosure pilot program involving 13 banks in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Under a guideline issued by the central bank, each pilot bank must formulate a working plan for environmental information disclosure by March 15 and submit an annual report for 2020 by June 30. Starting in March 2022, pilot-program banks will be required to submit an annual environmental information disclosure report for the previous year.

One of biggest challenges is incomplete disclosure of environmental information by enterprises that banks are exposed to, said Le Yu, senior manager at ICBC’s risk management department. Much of the data is qualitative, not quantitative, he said.

The CBIRC is trying to draft information disclosure guidelines on green financing to make it easier for banks and insurers to disclose information and accept supervision, Le said. The proposed disclosure will include how much of each asset class can be put in a high-risk emissions category and how much mitigation benefits are supported by green financing, he said.

“It would be better if we can make disclosure mandatory,” Le said. “But if we can’t, voluntary disclosure should go initially. Guidelines like this will help to push things forward.”

The PBOC’s Ma suggested that regulators should introduce mandatory environmental information disclosure requirements for listed companies as soon as possible.

Incentives are needed

Such disclosure will add costs for enterprises. Under strong policy support and incentives, companies could certainly comply, Industrial Bank’s Lu said.

In previous development of green financing, there were too many constraints and too few incentives for financial institutions, Lu said. For example, while the whole of society benefits from green projects, financial institutions that support such efforts “have nowhere to collect the money,” Lu said.

In its Fourth Quarter Monetary Policy Implementation Report released Feb. 8, the PBOC suggested how to build a policy incentive and constraint system, including the use of inclusive refinancing and rediscount tools to increase financial support for technological innovation and development of green projects. It was the first time the central bank included green financing in the scope of support using inclusive refinancing and rediscount tools, which offer lower interest rates.

The State Council, China’s cabinet, has also issued a guideline to give green finance greater weight in how financial institutions are evaluated as policymakers aim to make it easier for environmentally friendly projects to obtain financing.

Another incentive option is to reduce the risk weighting of green assets for commercial banks. However, opponents argue that lowering risk weightings could increase financial stability risks as some low-carbon projects are less liquid, longer-term and relatively riskier.

A major reason why the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has yet to push ahead such a move is that there is not enough data on whether green financing has a lower default rate, said Zhu Jun, director of the International Department of the PBOC.

But the central bank’s Ma said China is better prepared to reduce the risk weighting of green assets as it has seven years of green financing data. Green financing has a default rate of 0.4%, compared with an overall default rate of 1.8% in China, according to Ma.

China’s national carbon trading market began its first “compliance cycle” Jan. 1, marking the official opening of the market. Under the cycle, which will at first be limited to domestic thermal power generators, 2,225 companies in the industry have until Dec. 31 to meet the requirements set by the government for carbon emissions.

Wang Zikai contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com).

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Follow the Chinese markets in real time with Caixin Global’s new stock database.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR