In Depth: China’s Launch of World’s Largest Carbon Market Has a Sputtering Start

China has launched its long-awaited national carbon trading market, marking a major step by the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter to realize ambitious climate goals.

With more than 2,000 power generation companies initially participating in the national emissions trading scheme (ETS), the market aims to put a price on greenhouse gas emissions to create pressure to reduce the amount produced.

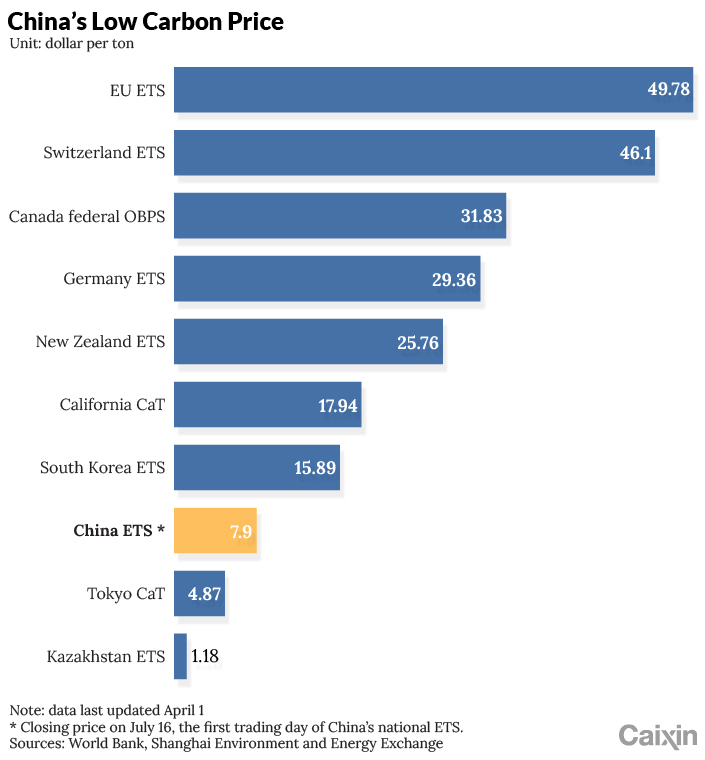

These companies’ total annual carbon emissions are expected to reach 4.5 billion tons (link in Chinese), making the national ETS the largest in the world. On July 16, the ETS made its debut in Shanghai with an opening price of 48 yuan ($7.40) per ton of carbon dioxide equivalents. Its first transaction was sealed at 52.78 yuan per ton right after the market opened, higher than expected. Since then, the closing price has been hovering above 50 yuan, though well below the levels in many other countries.

Government officials have shown confidence in the ETS’s prospects. However, experts said the scheme still has a long way to go before reaching maturity.

In the ETS’s hasty launch, the government has yet to fully clarify the responsibilities of different regulators supervising the market. And as financial institutions and businesses outside of the electricity sector haven’t been allowed to directly trade on the market, many have questioned whether it’s liquid enough.

|

Pressure to cut emissions

An ETS is a tool that many countries and regions have adopted to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The EU launched the EU ETS, the world’s first international ETS, in 2005. Later, countries including South Korea, New Zealand and Switzerland, as well as some parts of the U.S., followed suit.

China had already established regional ETSs in eight provinces and cities, including Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen. Seven of the ETSs started trading in 2013, while the one in the eastern province of Fujian kicked off three years later. In 2015, China pledged to roll out a national ETS (link in Chinese) in a bid to unify the scattered regional markets.

Under an ETS, the government sets quotas for the amount of greenhouse gases that companies can emit during a certain period. Those that spew less greenhouse gases into the atmosphere than permitted to can sell their remaining quotas via the system in the form of carbon credits, while buyers are those who emit more than their allotments and want to avoid paying fines.

In China, an initial cohort of 2,162 power generation companies (link in Chinese) participate in the national ETS. Under the total quota limit, the companies in aggregate are expected to be allowed to emit more than 4 billion tons of greenhouse gases (link in Chinese) in 2021. They are required to (link in Chinese) report this year’s actual amount of emissions to regulators by the end of next March.

Industry insiders said the quota limit is generous, indicating the government’s soft stance on reducing emissions in the early days of the ETS. Similarly, the annual quotas (link in Chinese) for China’s major power generation companies in 2019 and 2020 both reached more than 95% of their actual emissions, the insiders estimated. Many expected the government to gradually tighten the quota in the coming years, and auction an increasing proportion of it, shifting away from the current approach of giving it away for free.

“China’s plan is to establish the carbon market first and then gradually improve it,” said Zhang Xiliang, a Tsinghua University professor specializing in energy and climate issues.

Even so, the power firms have felt the heat from the ETS. Before the scheme’s launch, the China Electricity Council, an industry group, held several meetings with its members to discuss what price is proper for carbon credits trading on the ETS, a knowledgeable source at a major electricity group told Caixin. The companies proposed setting the initial price at 25 yuan per ton, but the Ministry of Ecology and Environment disagreed and set a higher price at 48 yuan per ton, the person said.

Even at a lower price of 30 yuan per ton, the cost of reducing carbon emissions would make up an estimated 5% to 25% of company’s total power generation expenses, a huge burden, a carbon asset manager at a state-owned power company said.

Energy-intensive power-generating facilities are expected to take an especially hard hit from the national ETS. Some facilities emit 1 million tons of greenhouse gases more than their annual quota limits, meaning additional costs of about 50 million yuan, based on a price of 50 yuan per ton for carbon credits on the ETS, said Xiao Yonghui, general manager of a carbon asset management firm under State Power Investment Corp. Ltd., one of China’s five major electricity generators.

In the face of soaring carbon costs, several power generation companies trading on the ETS have pledged to accelerate a strategic pivot to new energy, including China Huaneng Group Co. Ltd. and China Huadian Corp. Ltd., another two of the “Big Five” power firms.

Read more

Caixin Explains: How China’s New Carbon Market Will Work

An underdeveloped market

Although the ETS has begun to put pressure on emissions-intensive firms, analysts believe there’s a lot of room for improvement.

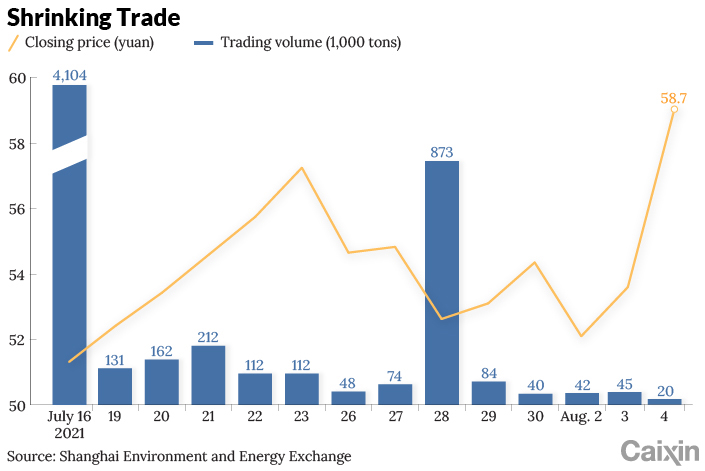

One point is that the market is not liquid enough. On the ETS’s first day of trading, carbon quotas equivalent to about 410,000 tons of emissions changed hands, but trading volume slumped the following day and has remained below 120,000 tons for most of the trading days by far, with Wednesday recording only 20,000 tons.

|

Analysts said the problem is that currently only one type of company is trading on the ETS, and that the trading volume will probably not jump until the end of the year, when some firms have no choice but to buy carbon credits to offset their emissions. Meanwhile, some companies are reluctant to sell quotas for now as they hope higher prices in the future to bring them juicier profits.

The government has plans to gradually include companies from seven other industries: petrochemicals, chemicals, construction materials, steel, nonferrous metals, papermaking and aviation. But this is likely to take some time.

The absence of financial institutions on the ETS also contributes to the market’s liquidity problem. Unlike many other carbon markets, such as the EU ETS, where financial institutions are major participants, China has not yet allowed them to directly participate, which some interpret as an effort to ensure market stability and keep financial risks in check. “China’s idea is to build the carbon market first, and gradually introduce financial institutions after it sets up solid regulations,” said Zhang of Tsinghua University.

A source close to the central bank said that allowing financial institutions to participate could have delayed the carbon market’s launch because regulators would need time to establish relevant rules. “Considering that the launch of the national carbon market has been delayed, it was more important to launch the market first,” the source said.

Some expect that the government will eventually allow financial institutions to trade on the carbon market. In addition, China’s newly built Guangzhou Futures Exchange is accelerating its efforts to launch a carbon futures market.

It may take seven to eight years for the national ETS to mature, given the time needed to introduce an auction mechanism for carbon quotas and to allow the trading of relevant financial derivatives, said Mei Dewen, general manager of the China Beijing Green Exchange, the operator of the regional ETS in the capital.

Read more

In Depth: China Wants Its Next Futures Exchange to Run a Lot More Like a Company

In addition, analysts called for the government to further improve laws and regulations to better oversee the national carbon market. Currently, the market is regulated by the environmental ministry’s Measures for the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading (Trial) (link in Chinese), which took effect Feb. 1. However, given the limited power of the ministry, the measures did not specify the responsibilities of other government departments. The State Council, the country’s cabinet, is now designing higher-level carbon market regulations (link in Chinese) to supplement what’s missing.

The government also needs to strengthen the legal punishments for fabricating emissions data, said Qian Guoqiang, a deputy general manager at SinoCarbon Innovation & Investment Co. Ltd., an investment firm focused on energy and the environment. There have been cases on regional ETSs in which some third-party verification agencies faked the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by their clients at a figure lower than the actual level. Qian suggested the government appoint several reliable third-party testing agencies to verify the emissions reported by companies, or require authorities to conduct random inspections.

Meanwhile, longer-term policies are required to give carbon market participants stable expectations. “We hope authorities can clearly specify (policies) as soon as possible after the launch of the national carbon market,” Qian said.

Contact reporter Tang Ziyi (ziyitang@caixin.com) and editor Michael Bellart (michaelbellart@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR