In Depth: What’s Holding Back Carbon Capture in China?

China’s bold pledge to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2060 has set the stage for the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter to boost technologies that absorb planet-warming carbon dioxide from pollution sources, put it to industrial use and stop it from entering the atmosphere.

But the Asian giant faces serious challenges to ramping up carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), with high costs, weak economic incentives and rickety legal support hindering the industry’s growth — problems compounded by the shock of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Although CCUS cannot single-handedly cut carbon emissions at the scale needed to reverse climate change, experts said the suite of techniques is crucial for reaching carbon neutrality and winning the global battle against climate change as it can bolster other measures like renewable energy and hydrogen production.

“There is no way for China to realize carbon neutrality (on schedule) without CCUS,” said Li Xiaochun, a professor at the Institute of Rock and Soil Mechanics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

|

Minor player, major potential

While Chinese scientists view many CCUS technologies as mature, the country currently uses them on a fraction of its total emissions.

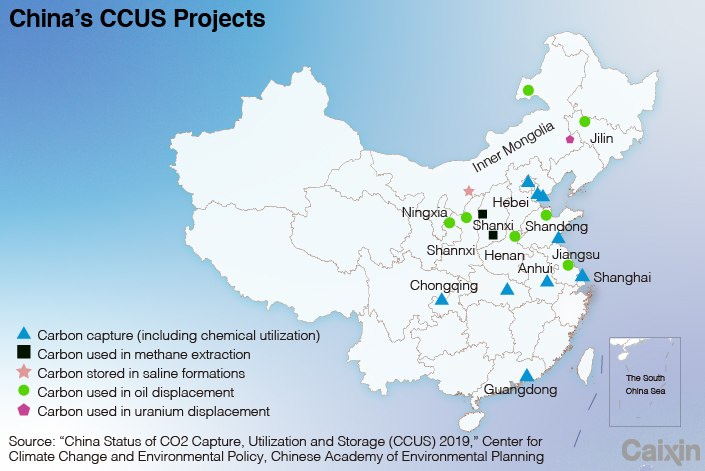

The world’s second-largest economy had undertaken nine carbon capture demonstration projects and 12 utilization and storage projects by the end of last year, according to a report published earlier this year by a research group affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Environmental Planning (CAEP), a Beijing-based think tank.

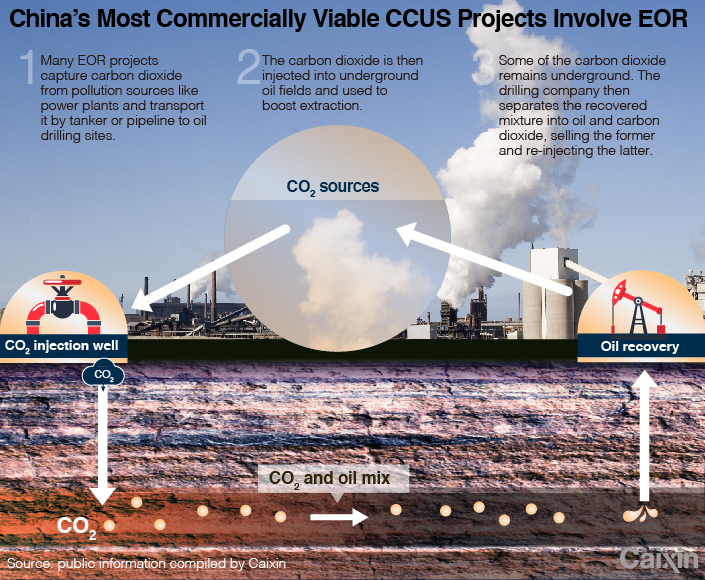

The most commercially viable projects generally involve enhanced oil recovery (EOR), whereby carbon dioxide is captured — for example, from fossil-fuel power plants — and injected into underground oil fields, boosting oil recovery and removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Research indicates that China’s CCUS sector has high potential. The country could theoretically deploy different aspects of the technology at carbon-spewing power plants as well as across other huge, but otherwise hard-to-decarbonize, sectors like steel, chemicals and cement.

Additionally, China could store an estimated 8 billion tons of carbon dioxide in oil and gas fields and potentially hundreds of times more in underground saline formations, according to a report released earlier this month by the Global CCS Institute, an international think tank. By comparison, the country’s total annual carbon emissions amounted to 10 billion tons in 2018.

With the right backing from the government and investors, China’s CCUS industry could expand significantly in the coming years, said Brad Page, the institute’s CEO, in an interview with Caixin. “Increasingly, the volume is being turned up,” he said. “Its time is coming.”

Yet the fact remains that CCUS currently contributes very little to China’s emissions cuts. The country currently stores “about one ten-thousandth of annual total emissions,” according to the CAEP-linked report. It’s a global issue: Even the United States, an industry pioneer, has the capacity to capture less than 0.5% of its annual net carbon emissions, according to a Caixin estimate based on figures from the Global CCS Institute and the U.S. Department of Energy.

|

A costly innovation

High costs restrict CCUS in China to a handful of profitable industrial applications and drag on the sector’s growth — a problem compounded by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

The upfront expenses deter both state-owned and private entities from investing in CCUS in the absence of concerted pressure to decarbonize, said Yan Qin, a carbon analyst at data provider Refinitiv. “From a market perspective, CCUS is among the last batch of abatement measures you would implement.”

The cost of CCUS differs according to the nature of each project, but the capture stage is typically the most expensive. Capturing low concentrations of carbon dioxide in China last year cost between 300 yuan ($46) and 900 yuan per ton, transporting it by tanker cost between 0.9 and 1.4 yuan per ton per kilometer, while using and storing it carried further highly variable costs, according to the CAEP-linked report.

In normal times, that’s where EOR comes in. According to the report, as long as crude oil prices hover above $70 per barrel, Chinese companies can balance the costs of CCUS against the revenue generated from the oil it helps to extract.

But these aren’t normal times. Since pandemic-induced global economic shutdowns triggered a prolonged decline in oil prices, Chinese companies have found EOR far less profitable.

The price collapse threatens the sector’s medium-term outlook, with the International Energy Agency stating in a September report that “an extended period of low oil prices and demand would undoubtedly undermine planned investment in CCUS projects linked to EOR.”

Legal barriers

China’s half-baked CCUS laws and regulations are a major impediment to the sector’s progress despite increasing attention from the government over the last decade, experts said.

The country issued guidelines (link in Chinese) on a prospective national strategy for CCUS development in 2013 and later included the technology in a flurry of industrial and environmental policies at both national and local levels.

But unlike its approach toward other climate-friendly innovations like renewable energy, China has not enshrined CCUS use in law — in contrast with the U.S., where a fuller-formed legal framework regulates certain aspects of CCUS, particularly transportation and storage.

A paper published last year in the peer-reviewed journal Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews said China’s diffuse patchwork of rules fails to specify the rights and obligations of participants in the CCUS sector as well as the parties responsible for crucial work like technical guidelines, construction plans and financing schemes — an approach that “weakens the authority of the policy framework.”

Although the National Development and Reform Commission, the environment ministry and some local governments have enacted CCUS policies, “they aren’t compulsory or supported with clear budgets,” said Li, the CAS professor. “Even the good policies aren’t particularly good.”

Room to grow

To foster the development of its CCUS sector, China should fortify its laws and regulations, cultivate a more dynamic market for the technology and provide stronger financial incentives, experts told Caixin.

The proposals carry weight at a time when government officials are sketching both the next five-year plan, which will shape national policy through 2025, and broader targets for 2035.

Page, the Global CCS Institute’s CEO, said he hoped China would outline “the sectors that the administration believes over the next five years should be taking steps toward implementing (CCUS) as part of this bigger program to get to carbon neutrality,” as well as reemphasize technology development in hard-to-decarbonize sectors, “because that’s where the cost is.”

Li said he expects the government to consider compulsory, enforceable legislation requiring enterprises to control carbon dioxide pollution in a similar way to existing curbs on sulfur and nitrogen emissions — a move that could stimulate CCUS uptake. “Unless our laws obligate them to address the issue, companies won’t take any real action,” he said.

Wei Ning, a professor also affiliated to the CAS’s Institute of Rock and Soil Mechanics, suggested China could consider implementing incentives akin to the U.S.’s 45Q federal tax credit for companies that sequester carbon dioxide for EOR or geologic storage.

Several experts said China could use financial subsidies to foment vitality in its CCUS sector. Li Jia, an associate professor at the China-U.K. Low Carbon College of Shanghai Jiao Tong University who is not related to Li Xiaochun, drew a parallel with how government subsidies helped to drive down the manufacturing costs of solar photovoltaic panels in the last decade and spurred their nationwide rollout.

“CCUS has never received a similar amount of subsidies, and there is no similar policy to help its deployment,” Li Jia said. “It doesn’t mean having them for a lifetime — a five- to 10-year supporting framework would dramatically reduce the cost of capturing carbon dioxide.”

Multiple experts said China’s nascent national carbon market could help to incentivize polluting enterprises to deploy CCUS. But Qin, Refinitiv’s carbon analyst, said the market’s expected gradual phase-in and initially generous carbon prices make it “unlikely” to drive a major expansion in the technology’s use in the short term, even though it will “make these industries more accountable for their emissions.”

Barring game-changing technological advances, China’s CCUS sector will likely achieve a “modest expansion” over the next 15 years, Qin predicted. “There will be more pilot projects based on technology subsidized by the government or state-owned enterprises,” she said. “(But) I can’t see a big breakthrough before 2035.”

Contact reporter Matthew Walsh (matthewwalsh@caixin.com) and editor Michael Bellart (michaelbellart@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR