Opinion: Philanthropy Needs to Move Beyond Grants

Philanthropy has developed in recent years as a widespread, systematic practice in Asia. The region’s remarkable growth has meant the emergence of the ultra-rich and a distinct socioeconomic middle class. At the same time, many still recall a time when their families did not have enough. There is therefore a strong desire to give back.

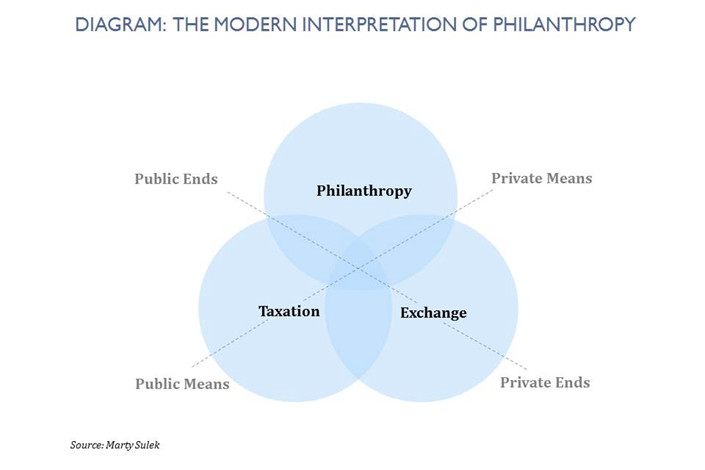

Philanthropy can be conceptualized as a private means to achieve public ends (and in parallel, government taxation as public means to public ends, and market exchange as private means to private ends). In Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland, signs abound that philanthropy is thriving. When in 2014, the family of Hong Kong-born investor Gerald Chan provided a $350 million gift to the Harvard School of Public Health, it was the largest single gift ever received by the university.

And according to Forbes China’s 2018 Philanthropy List, the 100 most generous entrepreneurs donated around $2.5 billion to charitable causes in 2018, representing a 66% annual increase in donations.

However, is philanthropy in its current form truly effective in delivering tangible, positive societal outcomes? Sure, there are numerous cases where a “pure grant” makes sense, where philanthropists donate money without any expectation that they will see the money they’ve donated ever again. For example, in the areas of disaster relief, research, policy advocacy and culture, grants have often played a crucial role given the typical lack of revenue streams attached to such activities (whilst the social benefit that may be derived from undertaking them could be high).

However, the expectation of a negative 100% return (the nature of a “pure grant”) sometimes means there is insufficient follow-up in terms of how the donation is actually used, let alone what impact was ultimately achieved. A recent article noted that philanthropic activities of the super-rich in Hong Kong are largely unrecorded, with no specific research to provide an in-depth picture of the impact of their donations. In 2015, Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, commented that “giving donations to charities is harder than earning money,” as it is tough to figure out to whom one should give. With the growth of philanthropy in Asia, it is clear that enabling philanthropic dollars to be used more strategically and effectively to deliver positive impact will be an increasingly important endeavor.

A recent development, especially promoted by the millennial generation as they assume roles in philanthropic organizations, is the increasing use of business tools — such as key performance indicators, transparent accounting and sound management — to instill greater rigor in resource allocation and impact delivery.

The use of profit as a motive in organizations focused on delivering social and environmental impact is also becoming more common. This has led to the growth of social delivery organizations and enterprises sitting at various points on the profit-nonprofit continuum. In mainland China, the social enterprise scene is taking off. Areas such as elderly services and special education are ripe for scalable social business models. In Hong Kong, organizations such as The Yeh Family Philanthropy have been supporting courses on social entrepreneurship to empower young talent in building their social business ideas.

|

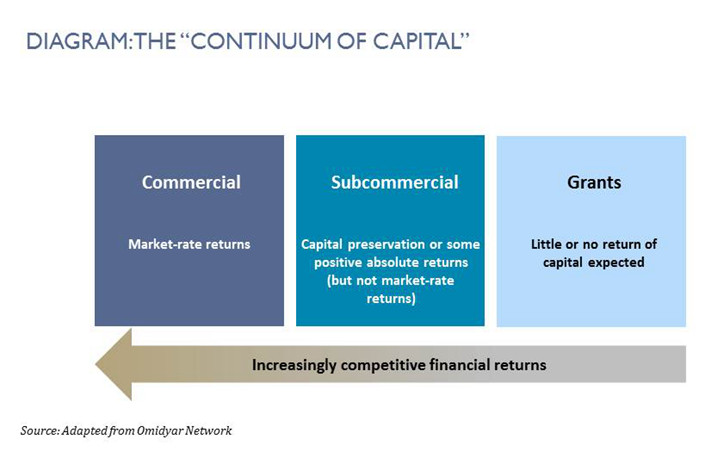

To meet the capital requirements of this new crop of socially-motivated organizations, a continuum of funding approaches is also emerging, from the “pure grant” funding approach all the way to sub-commercial or even commercial investments, which generate varying degrees of financial returns alongside social and environmental impact.

Here is an example of the roles different types of capital may play. Take MicroEnsure, a social enterprise providing insurance to over 40 million customers in low-income households in Asia and Africa. A grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation fueled the non-profit’s initial expansion, enabling it to test and build products tailored to the needs of low-income customers and scale from 2 million to 15 million subscribers.

Once it succeeded in establishing strong consumer demand, the business moved along the continuum, attracting sub-commercial debt and equity investment from Omidyar Network and others, which helped it to transform from a non-profit to a sustainable, for-profit social enterprise. Omidyar Network was willing to accept lower financial returns in return for MicroEnsure’s potential to seed an insurance market for low-income households. Once the viability of the business model was proven, more commercial investors such as AXA came on board, supporting the enterprise to further expand.

In the United States and Europe, some of the leading philanthropic players are adopting funding approaches across the continuum to enable the scaling of impact. Most recently in March, the Rockefeller Foundation, Omidyar Network and the MacArthur Foundation launched the Catalytic Capital Consortium, initially with $150 million of capital, to fund the riskiest and typically least financially rewarding slice of impact investments that sits in the “sub-commercial” range of the continuum.

The aim is to unlock billions, or even trillions, of further investment into solutions that achieve the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, by providing investment capital that is patient, risk-tolerant, concessionary, and flexible. In the words of the MacArthur Foundation’s President Julia Stasch, the idea is that this capital can “help create proof points of future profitability,” and “be part of a blended approach that makes it possible for financing to be available to populations and places that would not otherwise be possible,” much like in the case of MicroEnsure.

Despite this progress, the adoption of a “beyond grants” approach by philanthropic organizations in Asia, including in Hong Kong and in mainland China, is not widespread. There is a bifurcation in that philanthropic organizations typically exclusively use grants to “do good,” whilst investments made from their endowment typically focus solely on maximizing financial returns (with little to no regard for the associated positive or negative impact of the investment). In essence, the “continuum of capital” approach is rarely applied. This seems like a missed opportunity. Given the size of endowment pots, a small proportion dedicated to investments that generate both financial and social or environmental returns would be a relatively low-risk endeavor, and would enable more philanthropic assets to be used to further the social and environmental mission of philanthropic organizations.

To help organizations embark on this “beyond grants” journey, a starting point is to support the development of platforms and networks where philanthropic funders can share information about different financing approaches and explore co-financing opportunities. In this respect, RS Group in Hong Kong, a family office employing a “total portfolio approach,” which seeks to manage capital allocations across asset classes to “maximize an appropriate mix of social, economic and environmental performance,” has established the Sustainable Finance Initiative to encourage conversation and shared learning between funders.

In addition, supporting the development of a range of analytical capabilities within philanthropic organizations (and in the broader ecosystem) will enable better sourcing and due diligence of grant and investment opportunities, and allow for more robust assessments of both the funding opportunities’ potential impact, as well as the appropriate financing approach along the continuum to deploy.

Continued monitoring of the outcomes generated during the funding period — regardless of whether it is a grant or an investment — alongside working closely with grantees and investees to make use of this data to deliver better services and products, will help generate learning as to what is and what isn’t working, and ultimately enable the delivery of greater societal impact. This will help lay the foundations for philanthropic organizations in Asia to play an even more catalytic role in the achievement of social and environmental impact.

Diane Mak is the incoming Senior Director of Impact Solutions at Y Analytics. She was previously Director of International Development at Social Finance Limited. Mak is a 2018 Asia Global Fellow at the Asia Global Institute, the University of Hong Kong.

If you want to submit an opinion piece to Caixin Global, please send an email to editor Wu Gang (gangwu@caixin.com.)

- 1Weekend Long Read: Can India Become the World’s Next Manufacturing Powerhouse?

- 2Chinese Localities Adopt ‘Sell Everything to Save the Day’ Policy to Ease Debt

- 3IBM Pulls R&D Units Out of China in Latest Withdrawal by U.S. Firm

- 4Cover Story: Chinese Brokerages’ Dual Roles in Bond Market Sparks Concern for Conflicts of Interest That Raises Systemic Risk

- 5Commentary: IBM’s Sudden China Layoffs Tarnish Reputation of ‘Foreign Company Culture’

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas