China is in the midst of a massive decarbonization campaign.

There was an obvious trigger. In September 2020, President Xi Jinping made a commitment that China will achieve peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and become carbon neutral before 2060. The so-called “dual carbon” goals, sometimes referred to as the 30-60 targets, are one of the priorities influencing the central government’s development strategies. They are expected to bring trillions of dollars of investment opportunities and help advance emissions-reduction technologies and low-carbon industries.

Here are key things you need to know about how China plans to meet its dual carbon goals, as well as the challenges that lie ahead.

Facts and goals

The world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter

In 2005, China surpassed the U.S. to become the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide and is now responsible for about one-third of global annual carbon dioxide emissions. In short, it is at the forefront of the global push to slash carbon emissions and contain climate change.

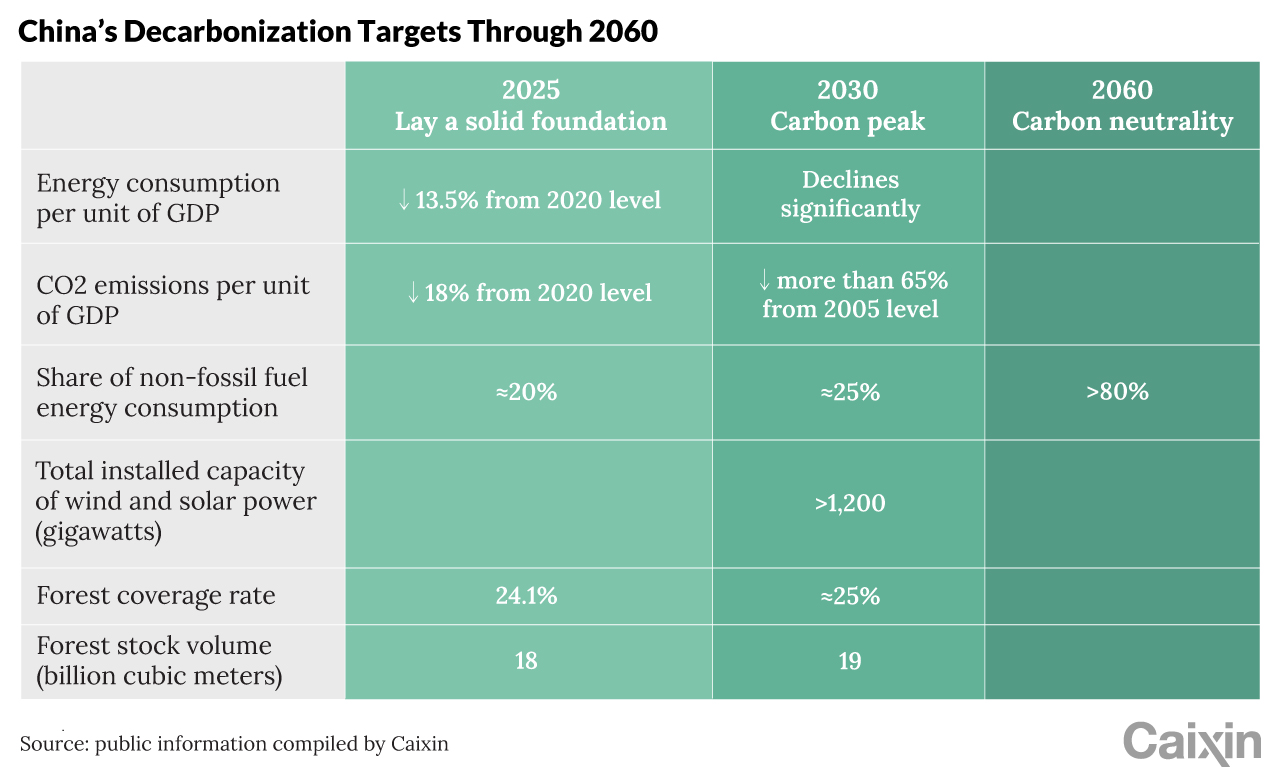

Cutting emissions will not be easy. Coal made up more than half of China’s total energy consumption in 2020. The country has pledged to raise the share of non-fossil fuels in its energy consumption to about 25% by 2030 and more than 80% by 2060, well above the 15.9% in 2020.

As the world’s manufacturing powerhouse, China requires a lot of energy, especially given that most of its manufacturing industries sit at the middle and lower end of the global industrial chain. Also, the fact that some developed countries have relocated their carbon-intensive production chains to China has exacerbated the nation’s environmental crisis. Today, there are similar concerns about China’s expansion into other developing countries, and its relocation of high-emission projects overseas has drawn scrutiny.

Meanwhile, China’s rapid urbanization has also contributed to rising emissions, as the process accompanied higher demand for energy-consuming industrial products such as steel, cement and automobiles. Urbanization is set to continue in China. Domestic policymakers aim to raise the national urbanization rate to 65% by 2025, up from 63.89% in 2020 and 49.68% in 2010, official data showed.

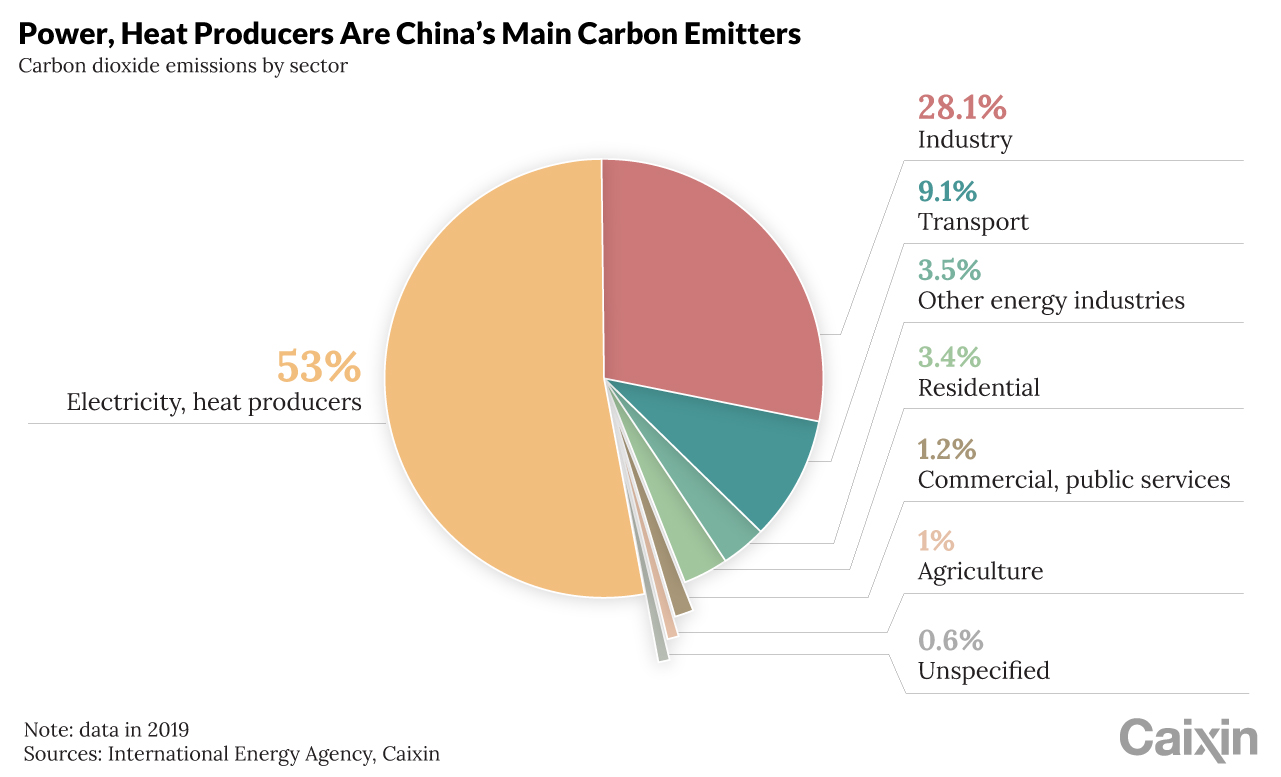

Those undercurrents have shaped the country’s sources of carbon emissions. In 2019, the power generation and heating industries contributed more than half of China’s total emissions, with industry accounting for 28.1% and transportation coming in at 9.1%, according to latest annual figures from the International Energy Agency.

Global consensus and China’s goals

World leaders need to cooperate to fight against climate change. Recent frequent weather catastrophes highlighted the urgency of more aggressive global efforts to contain global warming.

As of October 2021, 191 countries and the European Union had signed on to 2015’s landmark Paris Agreement, which set long-term goals including reducing global greenhouse gas emissions to limit the global average temperature rise to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-Industrial Revolution levels, and to pursue a more ambitious target of limiting the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The long-anticipated 26th U.N. Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, the U.K., that started on Oct. 31, 2021 is expected to bring the world closer in realizing these climate change goals.

For China, promoting low-carbon growth is in line with its planned transition to a more sustainable and innovation-driven growth model. Xi announced the dual carbon targets in September 2020, and then in December, he announced further detailed targets, including reducing carbon intensity — a measure of carbon dioxide produced for every unit of GDP — by more than 65% by 2030 from 2005 levels, compared with an earlier goal of 60% to 65%, which was announced in 2015.

Roadmap

In October 2021, China’s leadership released wide-ranging guidance (《中共中央 国务院关于完整准确全面贯彻新发展理念做好碳达峰碳中和工作的意见》) for the nations’ drive toward carbon neutrality over the coming decades, laying out general plans for different segments of its economy and a transition away from fossil fuels. The guidance is the “1” in China’s “1+N” carbon policy framework, consisting of one overarching plan and many detailed plans for specific sectors.

The guidance requires all future major decisions on economic planning, macroeconomic adjustments and industrial policies to be compatible with the carbon reduction goals, and should lead to full-blown green transformations, analysts said. It sets multiple targets as shown below.

Power crunch

Reducing the use of coal is among the challenges on the way to decarbonization. Since September 2021, there has been a squeeze on coal supplies due in part to stricter safety and environment requirements, and government efforts to rein in industrial overcapacity. Meanwhile, some local governments have ramped up efforts to curtail industrial energy use and meet Beijing’s energy consumption control targets. Such a situation has contributed to the recent power crunch that has hit industries and residents alike in many regions across China.

Click to read more about China’s power crunch

To support household power consumption for the winter, the government has taken a step back to stabilize coal supplies for the season. It rolled out measures including providing reserve coal to the market, and encouraging qualified coal mines to increase capacity.

Data is key

There is a lot of political will behind the decarbonization effort, and the deadline is pressing. But one hurdle is that some key data is incomplete.

For instance, the government uses 2005 as the baseline for its 2030 peak emission target, but it has never disclosed the amount of carbon emissions that year. That creates a hurdle for authorities to design emissions reduction plans, said Zhou Xiaochuan (周小川), a former governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) (中国人民银行). He reasoned that either relevant figures were not properly calculated back in 2005 or cannot be properly verified, or the government has them, but wants to delay the release to leave some room for making the goal attainable.

Regulatory framework

Who runs what

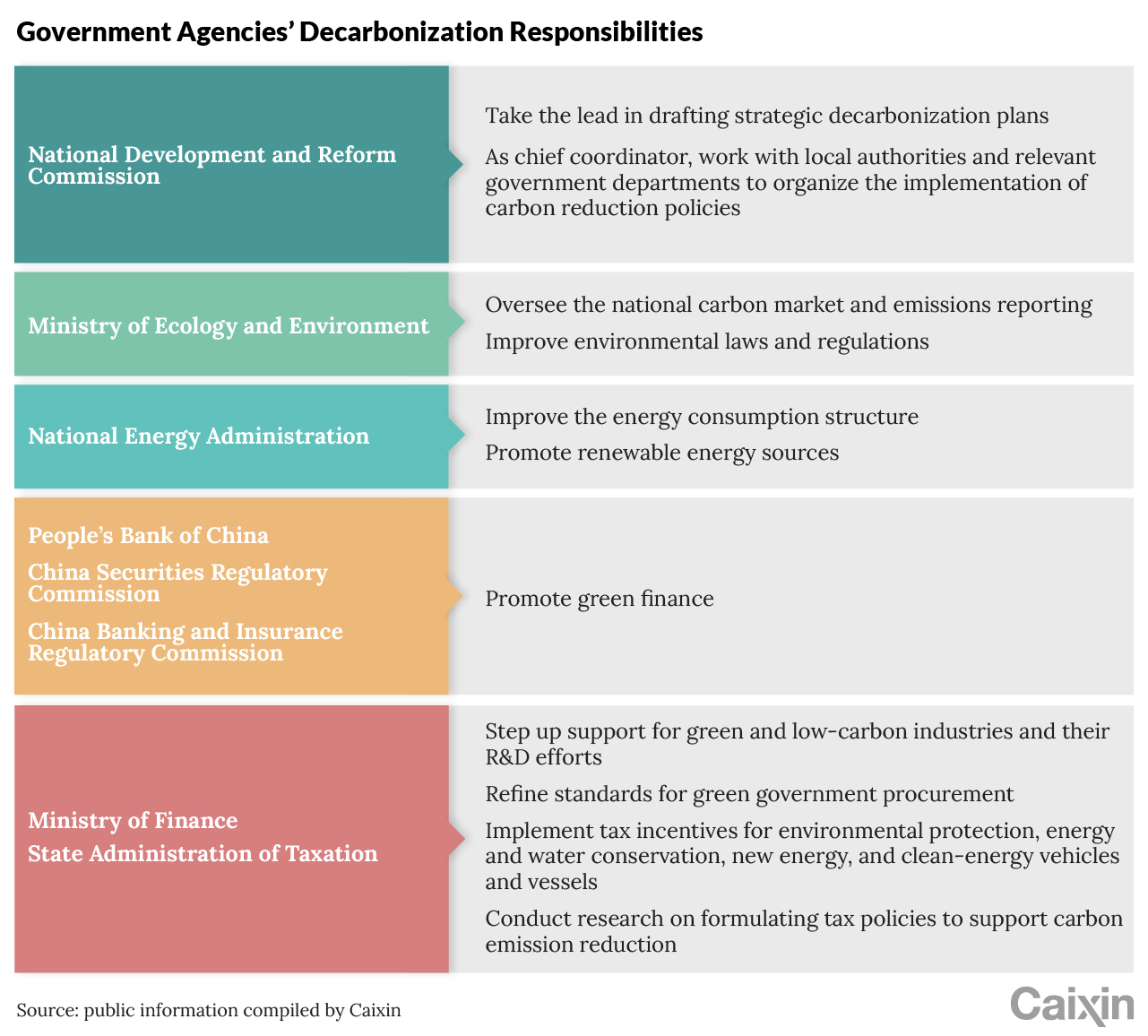

While there are many ministry-level departments and one group involved in regulating carbon policies, pretty much all government bodies will incorporate some carbon issues into their agenda.

The leading small group (LSG) on peak carbon and carbon neutrality (碳达峰碳中和工作领导小组) is the highest coordination mechanism to direct China’s emissions reduction work. In May 2021, the first plenary of the LSG was chaired by Vice Premier Han Zheng (韩正), who is also a member of the seven-member standing committee of the ruling Communist Party’s Politburo, China’s top decision-making body. Other political heavyweights attending the plenary included Vice Premier Liu He (刘鹤), State Councilors Wang Yong (王勇) and Wang Yi (王毅), and National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) (国家发展改革委) Chairman He Lifeng (何立峰).

The small group is a Chinese political mechanism that’s usually created to deal with critical or urgent issues that need high-level coordination and cooperation between different government departments.

The NDRC, China’s top economic planning body, is in charge of drafting overall strategic plans to achieve peak carbon emissions. It has announced the country will fulfill the dual carbon targets via six methods, ranging from adjusting the energy structure to promoting low-carbon technologies.

Another important government body is the central bank, which is responsible for crafting policies and incentives to guide financial resources to support green development. The central bank has pledged to improve classification standards for green finance and consider imposing requirements on financial institutions to disclose environment-related information.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) (生态环境部) is leading the effort in writing drafts and revisions of environmental laws and regulations. It now also oversees the country’s national carbon market, also known as the emissions trading scheme (ETS).

China’s carbon market

The national ETS

An ETS is a crucial step in reducing emissions of greenhouse gases.

Click to read more about China’s national carbon market

Click to read more about China’s national carbon market

China launched its national ETS on July 16, 2021, in Shanghai, the world’s largest so far. More than 2,000 power generation companies are trading on the market, which accounts for more than 40% of China’s energy-related carbon emissions.

Those power generation companies in aggregate are allowed to emit around 4 billion tons of greenhouse gases in 2021 under the total quota limit. They are required to report 2021’s actual amount of emissions to regulators for a review by the end of March 2022. Industry insiders said the quota limit is generous, indicating the government’s soft stance on reducing emissions in the early days of the ETS.

As of October 2021, the trading price of carbon credits had been hovering around 50 yuan ($7.81) per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent since the launch of the ETS — well below more than $50 in the EU ETS in the same period. And the trading volume has remained low since the launch.

Regional ETSs

Before the launch of the national ETS, China had already established regional ETSs in eight provinces and cities, including Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen. Seven of the regional ETSs started trading in 2013, while the one in the eastern province of Fujian kicked off three years later.

China will no longer launch any new regional ETS after the national one, and the current regional ETSs will be gradually “included” in the national ETS, according to draft regulations released by the MEE.

What can push up the carbon price, eventually?

- A reduced quota and the introduction of an auction mechanism

The government is expected to gradually tighten the quota limits, based on the past experience of the EU ETS and some regional ETSs in the U.S., industry insiders said. Also, many expected that the government will auction a growing proportion of the carbon quota, shifting away from the current approach of giving it away for free.

- Inclusion of more industries

The government has plans to gradually include companies from seven other industries into the national ETS: petrochemicals, chemicals, construction materials, steel, nonferrous metals, papermaking and aviation. That will help boost liquidity of the ETS and push up carbon prices.

China will likely include cement and electrolytic aluminum producers into the carbon market in 2022, and add all the seven sectors by 2025, said Zhang Xiliang, a Tsinghua University professor who specializes in energy and climate issues.

- Financial institution participation

The absence of financial institutions in the ETS contributes to the market’s liquidity problem. Unlike many other carbon markets, such as the EU ETS, where financial institutions are major participants, China has not yet allowed them to be directly involved, which some interpret as an effort to ensure market stability and keep financial risks in check.

Some expect that the government will eventually allow financial institutions to trade on the carbon market after it establishes certain trading rules to prevent financial risks. In addition, China’s newly built Guangzhou Futures Exchange is accelerating its efforts to launch a carbon futures market.

- Connecting the ETS with overseas markets

Zhou, the PBOC’s former chief, suggested that China’s national ETS could be linked with other carbon markets in the world in a manner that will boost market liquidity and rein in speculation. The stock connect program that links Chinese mainland and Hong Kong markets could serve as an example, he said.

Multiple analysts expect China’s carbon price to grow gradually in the coming years. It could reach more than 100 yuan in 2030 and around 350 yuan in 2050, according to forecasts by investment bank China International Capital Corp. Ltd. (CICC).

CER versus CCER

China started trading carbon credits with developed countries nearly two decades ago. At that time, the developed world was ramping up efforts to fulfill their emission-reduction commitments under 1997’s Kyoto Protocol, which did not put developing countries under any emission-cutting obligations. The background was that many developed countries’ carbon emissions had already peaked, while those of developing countries were still on the rise. The protocol establishes a clean development mechanism (CDM), which allows developed countries to earn certified emission reduction (CER) credits by investing in projects that reduce emissions in developing countries.

The CDM has helped developing countries like China get money to construct clean energy projects domestically and reduce emissions. As of April 1, 2021, China was home to 3,861 registered CDM projects, accounting for nearly half of the world’s total.

However, the CDM’s development has slowed in recent years due to decreasing emissions in developed countries, as well as the fact that developing countries have also been required to take responsibility for cutting their own emissions. Under such a scenario, China began looking to launch pilot ETSs and the China Certified Emissions Reduction (CCER) scheme, which is similar to the CDM. Companies can voluntarily use verified emissions cuts from their low-carbon and renewable projects to apply for CCER credits, and then sell the credits on ETSs to those who emit more than their quota limits.

Cover Story: The Green Finance Challenge Facing China’s Banks

Cover Story: The Green Finance Challenge Facing China’s Banks

Green finance

China has the world’s largest market for green loans by outstanding value, and second-largest market for green bonds. But it’s still not enough — the decarbonization transition will require a massive amount of capital, creating huge opportunities for green financing.

Green loans

On the back of government support, China’s green finance market has grown rapidly, though the market is still small and dominated by a single type of financing — green loans. Loans make up 90% of green financing, with bonds at 7% and stock funding at 3%.

At the end of 2020, China’s outstanding green loans reached $1.8 trillion, the highest in the world. The loans were mainly lent to transportation, renewable and clean energy industries.

Green bonds

At the end of 2020, China’s outstanding green bonds reached $125 billion, the second-highest globally. Currently, such bonds usually carry lower yields than ordinary bonds, meaning cheaper funding costs for green projects.

The dual carbon goals have brought new momentum to the issuance of green bonds. In the second quarter of 2021, investors traded 98.9 billion yuan worth of green bonds on the interbank market, the highest level on record, according to data provider CEIC.

China’s green bond market grew rapidly in 2016, allowing the country to overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest green bond issuer the same year — though some observers say that was partly thanks to China’s looser standards for defining green projects.

China has begun to bring its green bond definition more in line with those of the rest of the world. In April 2021, the PBOC announced the proceeds from green bonds will no longer be allowed to go to certain fossil-fuel projects.

Regarding international cooperation, on Nov. 4, 2021, China and the EU issued the “Common Ground Taxonomy — Climate Change Mitigation” — a classification system for environmentally sustainable economic activities — laying the foundation for better promoting overseas investment in China’s green bonds.

Carbon tax

Chinese authorities have long been mulling over the idea of imposing a carbon tax. If it goes ahead, it would certainly have a big impact on emissions reduction. For instance, a tax of $50 per ton on carbon emissions could generate domestic environmental benefits equivalent to more than 3% of China’s annual GDP in 2030, the International Monetary Fund estimated. Meanwhile, a carbon tax has the added benefit of boosting government fiscal revenues.

In July 2021, the EU announced a plan to levy a tariff on carbon-intensive imports such as iron and steel, fertilizer and electricity generation. The move fueled calls to roll out a carbon tax in China. Still, many are concerned that such a tax levy will add to the financial burden of businesses, which might end up passing on their increased costs to consumers.

Default risks

Some analysts estimate that the probability of default by China’s major coal-based companies will rise to 24% by 2030 from less than 3% in 2020, predicting that they will face rising fundraising costs and that some local governments will take overly aggressive measures to shut down carbon-intensive production lines in a bid to hit the dual carbon goals.

China’s top leaders said at a Politburo meeting in July 2021 that China will pursue its dual carbon goals in an “orderly” manner, and will correct any “campaign-style” carbon reduction measures employed by local governments. This is a signal that China intends to balance achieving its climate goals with keeping the economy stable.

Tech and innovation

Technologies are key in combating climate change. A few are especially important to China’s decarbonization strategy.

New-energy vehicles

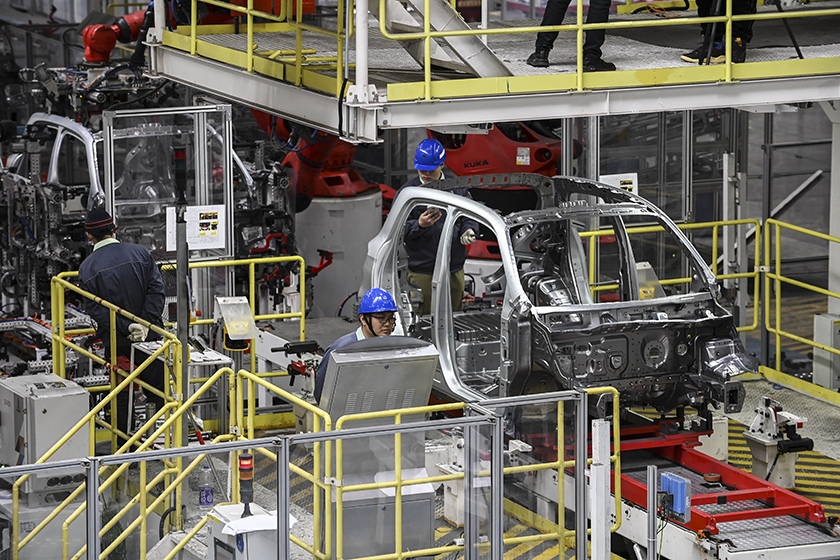

The transportation industry contributed 9.1% of China’s total carbon emissions in 2019, making it an important battleground for the country to conquer in order to hit its decarbonization goals. China set a goal for new-energy vehicles (NEVs) to make up 20% of domestic new car sales by 2025. The push into NEVs — a category that includes those that run solely on battery power or hydrogen fuel cells, as well as hybrids — is an important step to achieve the low-carbon transformation of the transportation sector. In China, automobiles contributed to more than 80% of the transportation sector’s carbon emissions in 2018, according to a report by investment bank CICC.

Aided by government subsidies that are expected to be stopped after 2022, NEVs have become a hot industry in China, with more and more tech companies jumping on the bandwagon.

Still, there are a lot of challenges facing the electrification of vehicles, including high cost of batteries, a lack of charging facilities and concerns about safety.

Energy storage

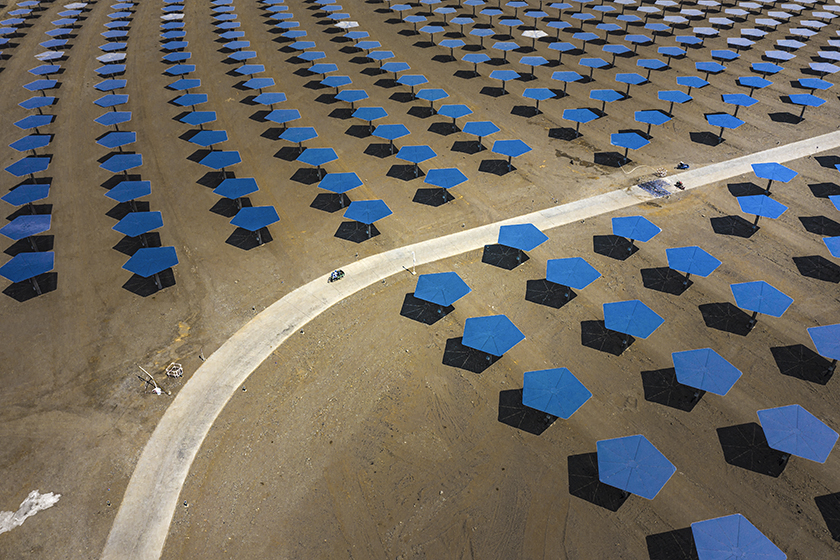

Energy storage is crucial for evening out the highly intermittent electricity generation of solar and wind power facilities. China has planned to install a total of more than 1.2 billion kilowatts of wind and solar power capacity by 2030, more than double the figure at the end of 2020.

But in China’s sunshine-rich western regions, some solar power arrays have had to let electricity go to waste due to their limited storage capacity. In 2019, Tibet lost nearly one-quarter of its solar-generated electricity, according to the National Energy Administration.

Now, China is transiting to a more effective battery storage method. The push has been driven by declining costs of materials for lithium-ion batteries and improved technologies that make a type of battery that provides reliable, long-term energy storage. In July, China announced a plan to increase its new-generation energy storage capacity to more than 30 gigawatts by 2025, about eightfold the figure at the end of 2020. The proposal signals strong backing for the planned expansions of solar and wind power generation.

Another solution to maximize energy utilization is to relocate production chains close to power generators. One example is that over the past few years, the southwestern province of Yunnan, which is known for its rich hydropower resources, has attracted many electrolytic aluminum producers. That said, the added power usage has strained the province’s own power supply, and even that of the southern coastal province of Guangdong, which relies heavily on Yunnan for electricity.

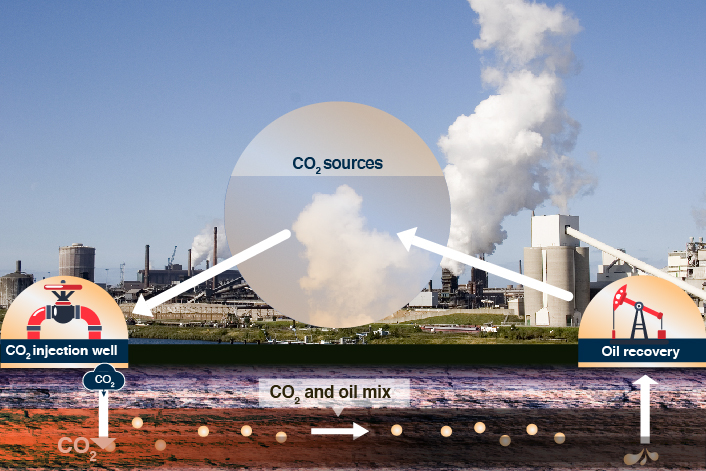

Carbon capture, utilization and storage

Carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) involves capturing greenhouse gas emissions from pollution sources like fossil-fuel power plants and gas fields and then injecting the captured gases underground for storage.

Research indicates that China’s CCUS sector has great potential, but it currently contributes very little to China’s emissions cuts. The country currently stores “about one ten-thousandth of annual total emissions,” according to a report by authors from multiple organizations including the Chinese Academy of Environmental Planning, a Beijing-based think tank. But this is a global issue: Even the U.S., an industry pioneer, only has the capacity to capture a tiny fraction of its annual net carbon emissions.

High costs restrict CCUS in China to a handful of profitable industrial applications and drag on the sector’s growth — a problem compounded by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

To foster the development of its CCUS sector, some expect the government to consider compulsory, enforceable legislation that requires companies to control carbon dioxide pollution in a similar way to existing curbs on sulfur and nitrogen emissions — a move that could stimulate CCUS uptake.

What to look out for

- What’s next for China’s carbon market?

China is planning to include companies from seven other industries in the market by 2025, including petrochemicals, chemicals and construction materials. The government will probably introduce an auction mechanism for allocating carbon quotas, and allow financial institutions to directly trade on the market.

- What can we expect from China at the COP26 climate conference?

The conference will be a crucial opportunity for all countries to strengthen their commitments.

Xie Zhenhua (解振华), China’s special envoy for climate change, said at a press briefing on Nov. 2, 2021 that he expects countries at the conference to reach a deal on carbon market rules according to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. The article includes mechanisms that allow the transfer of emission reductions units between countries.

(Published at 14.30 p.m., Nov. 10, 2021)

Follow Caixin Global’s carbon newsletter, and visit our special topic page on ESG and decarbonization.

Meanwhile, Caixin hosts the China ESG30 Forum and the China Net Zero Network.

The China ESG30 Forum is a high-level committee that brings together 30 experts annually to discuss ESG-related theory, policy and practical issues in China. The China Net Zero Network is a joint action carbon partner program to promote effective dialogue among stakeholders contributing to China’s carbon goals, sustainable growth and global climate action.

- Meet the Team

-

ReporterTang Ziyi

-

EditorsMichael Bellart | Bertrand Teo | Lin Jinbing

-

Contributing reportersZhang Yukun | Denise Jia | Han Wei

-

Contributing analystJasper Liu

-

Visual editorsYe Xueming | Zoey Xia

-

ProducersLi Hang| Zhang Hongtao

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with 财新

Sign in with 财新